The forced demolitions and evictions mostly take place on Beijing’s rural-urban fringes, home to millions of migrants from poorer part of the country who work in low-paid service jobs such as delivery.

The Chinese capital has seen a citywide campaign to demolish illegal dwellings following an apartment fire that killed 19 people earlier in November.

The campaign has led to public anger as it’s considered to be unfairly targeting migrant workers in a bid to cap Beijing’s population, an allegation the government has denied.

First Beijing pushed thousands of migrant workers out of the city in the name of safety. Now authorities are carrying out a parallel virtual eviction as well, removing references to China’s “low-end population” from the internet.

China’s internet, nevertheless, overwhelmingly resorted to the phrase “low-end population”-a term first used by the government but now used as shorthand to refer to prejudice towards migrants-to criticize authorities for driving these workers out of the city.

China’s censorship machines are rolling at full speed to shut down online discussions and criticism about the evictions. Leaked censorship directives show that Chinese news outlets are banned from publishing investigative reports and commentaries on the incident. Social media posts about the evictions have been mostly deleted.

On Weibo, China’s equivalent of Twitter, searches of the term “low-end population” in Chinese are entirely blocked “in accordance with relevant laws, regulations, and policies”, the site tells users. In the wake of the evictions, and a child-abuse scandal last week, the percentage of posts deleted on Weibo surged to a level higher than during a recently concluded Communist Party congress, according to Weiboscope, which monitors censorship on Chinese social media.

China’s most popular messenger app, WeChat, is censoring people’s chats about the evictions without them even knowing about it. During Quartz’s test on mainland China-based accounts, messages containing the phrase “low-end population” got scrubbed from group chats, and the sender received no notice telling her that her text had not reached the intended recipients.

The same applies to WeChat’s Moments feed, a Facebook Newsfeed-like feature-users won’t be notified that their posts or comments containing the sensitive term are not displayed to other users. One-on-one chats are not subjected to such censorship. This fits into WeChat’s patterns of censoring politically sensitive messages, as revealed by previous studies.

Messages containing the term “low-end population” are scrubbed from group chats on Wechat. (Screenshots from Wechat)

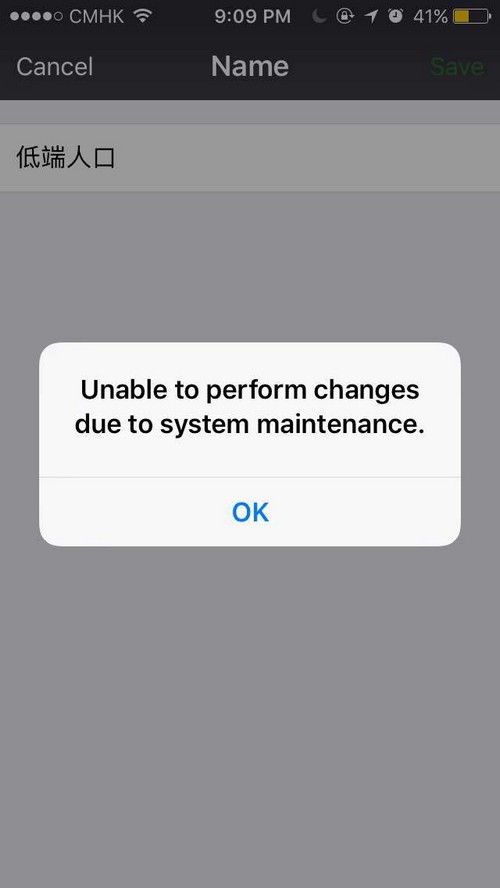

If a WeChat user tries to change her alias or the name of a group chat to a phrase containing the term “low-end population”, she gets a notice that such changes cannot be performed due to “system maintenance.” Changes to names without the term work just fine though.

WeChat users are not allowed to change their user IDs to “low-end population.” (Screenshot from Wechat)

On Alibaba’s Taobao, one of China’s biggest shopping sites, small business owners were touting hoodies with the slogan “low-end population”, but such offerings soon went off the shelves.

Weibo, Alibaba and Tencent, which owns WeChat, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Chinese authorities have long taken pains to control public discussion over contentious social events. This time, the scale-and ineffectiveness-of online censorship appears to be frustrating even to some propaganda workers. Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of the nationalistic state tabloid Global Times, wrote on Weibo (link in Chinese) to complain that the government is incapable of doing anything but deleting posts whenever it needs to guide public opinions.

“We don’t have midfielders, or defenders, but only a goalkeeper, so it’s hard to stop a goal from being scored”, he said, using a soccer analogy.

As more evidence of that, even two state-owned news outlets published rare commentaries questioning the hastiness of the forced evictions. “How can migrants quickly find another shelter that’s safe and where would they go to keep from the freezing cold in winter?” wrote China Central Television in a WeChat post.